Lean Leadership Habits That Drive Organizational Excellence

September 18, 2024Legend has it that when Toyota opened its first wholly-owned American manufacturing plant in Georgetown, Kentucky, they invited executives from the “Big Three” (GM, Ford, and Chrysler) to visit to see how Toyota made cars. A quick Google search neither confirmed nor denied if this is true, but either way, it’s a good story. It highlights the idea that there was a big difference in how the Big Three operated compared to how Toyota operated.

Toyota’s operations and the Toyota Production System (TPS) are legendary. They are the go-to example of Lean Manufacturing done right. That’s not to say TPS is perfect and never makes mistakes. The ongoing recall of over 100,000 engines in their flagship Tundra pickup truck is a good example of the fact that even the best make mistakes. However, despite occasional setbacks, TPS consistently stands out as a model of operational excellence.

So, what makes TPS so good?

The 5 Lean Principles Explained

If you’ve ever taken a Lean or Lean Six Sigma (LSS) class, you will have encountered many lessons on the tools of Lean. They are sprinkled throughout the traditional green and black belt curricula and organized around The Five Principles of Lean. Those five principles come from the book “The Machine That Changed The World” by Womack, Jones, and Roos and are: specify value, map the value stream, create flow, respond to pull, and pursue perfection.

Specify Value

The first principle is to identify your customers and specify what is of value to them. Put into operational terms, this is the concept of the Voice of the Customer (VOC). Various tools are taught and used to identify customers, gather information about what matters to them, and then convert that qualitative information into quantitative critical to quality characteristics and the associated metrics we use to track the state of the process. As Zig Ziglar puts it, “You can’t hit a target you cannot see, and you cannot see a target you do not have.”

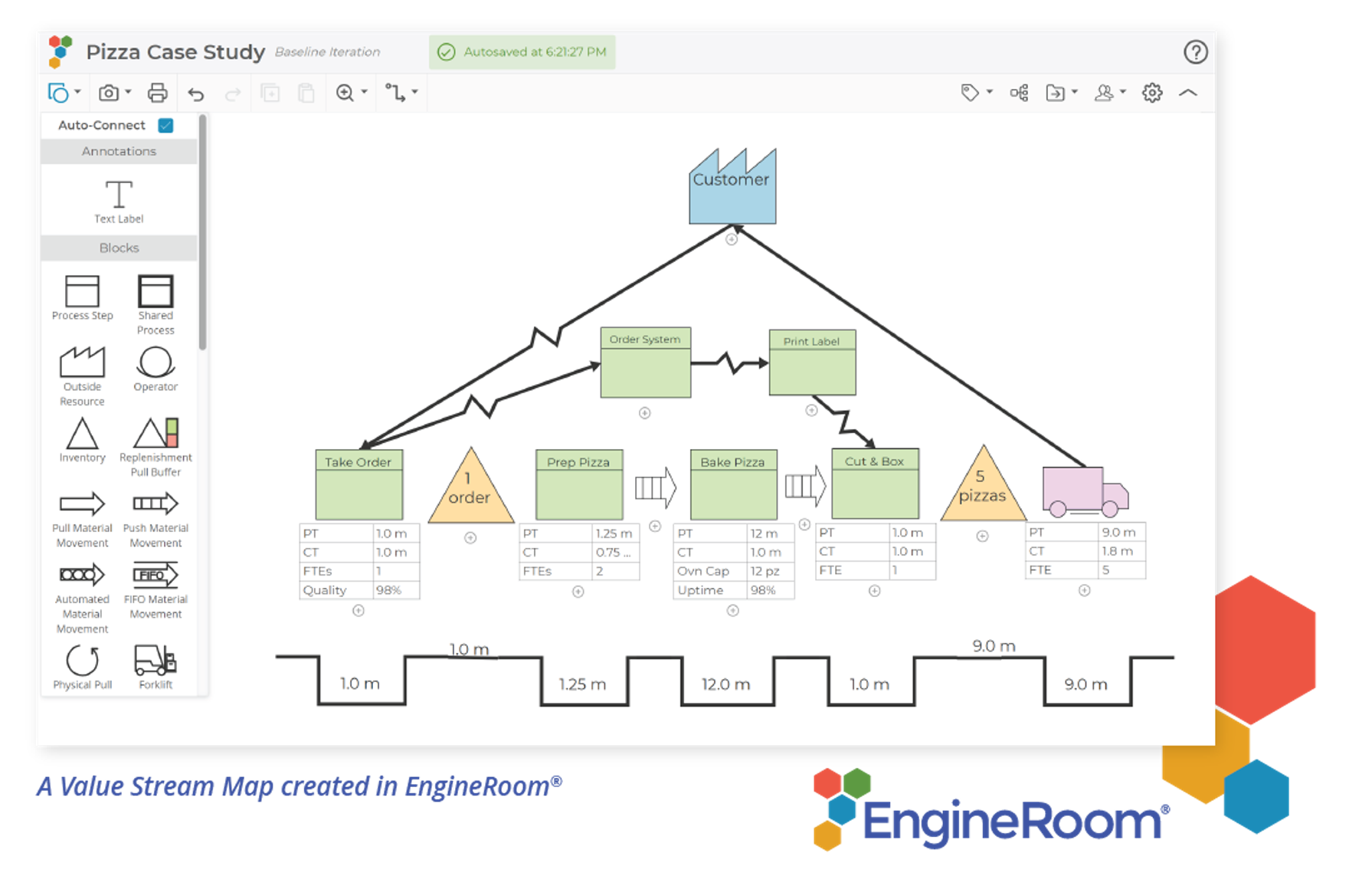

Map The Value Stream

Once we understand the customer and what they value, we need to understand what they experience as they interact with our organization. More often than not, that's a frustrating series of delays and handoffs from one department to another or suffering with poorly designed and manufactured products resulting from a frustrating series of delays and handoffs from one department to another. The customer experience is rarely limited to what a single department does. It consists of multiple steps that cross traditional departmental boundaries. The Value Stream Map allows us to "see" the process from the eyes of the customer for the first time. This visualization marks the beginning of another fundamental tenet of Lean – that everything should be visual. There shouldn't be any processes hiding in computers, or worse, a chaotic web of spreadsheets, sticky notes, and rules of thumb.

It's at this point that we need to start thinking about the eight wastes of Lean and understanding what parts of our process create value and what parts don't.

Create Flow

With the third principle of creating flow, we enter the world of design for manufacturing, work cells, and the famous single-minute exchange of dies (SMED). To create flow, we must remove barriers typically tied to departmental transitions and the safety net of large inventories, work, or things in process.

Respond to Pull

And now we arrive at the poster child of Lean – Pull Systems, and Just in Time (JIT) inventory. If you ask someone what Lean is, they will generally explain that it's the method of eliminating waste and pull systems – with the occasional reference to SMED if they come from a manufacturing background. In our teaching, we spend plenty of time talking about and teaching pull systems and JIT inventory.

Pursue Perfection

And with the final principle, we arrive at the idea of continuous improvement and error proofing. We teach that Lean is the relentless pursuit of perfection through small, incremental, continuous efforts at improvement. Lean is not revolutionary; it is evolutionary.

And so, with a healthy dose of lessons on each of the parts, our efforts at teaching Lean come to a close. And the probability of success in truly transforming an organization into a Lean organization and creating an environment that embraces continuous improvement also comes to a close. So what's missing? What is the secret that is hard to teach and harder to embrace and live?

Lean Leadership

Thinking of Lean as a System

Lean is a system. At the very least, we need to connect all of the tools of Lean and understand how they interact as a system of concepts and improvement opportunities. Early implementations of Just-In-Time (JIT) inventory systems often risked becoming JTL systems, Just-Too-Late, as they failed to understand the interdependence of SMED, defect prevention, replenishment pull buffer sizing, lot sizing, etc., as these all related to JIT. Simply lowering inventory without understanding the root causes of why that inventory formed in the first place was and remains a recipe for disaster.

So, Lean is a system, but what drives that system thinking and integration of continuous improvement efforts? One component is Lean Leader Standard Work (LSW). LSW is a set of tools and behaviors that create processes around leadership activities. Central to LSW is the concept of "Gemba Walks," derived from the Japanese word Gembutsu, meaning "the real place," or, more loosely, "where the real work is done."

The goal is to shift management and leadership activities from the office and the conference room to the shop floor, the hospital ward, or the retail floor. Managing from the office means managing from data in reports. Data in reports is, at best, an aggregation of data over a period of time and, at worst, a manipulation of data to support a position. Either way, information is lost, and decisions are made on an incomplete understanding of the state of the process and the customer's needs. The rules of the Gemba walk are as follows: go see, ask why, show respect, and start to hint at the true secret of Lean Leadership.

LSW is also the creation of management or leader standard work—simple, visual, repetitive processes that leaders follow every day. This includes the Gemba Walk but also other tools and routines, such as the various tiered huddle boards used to visualize the inventory of work moving through leadership processes. Daily stand-ups at the huddle boards focus on the state of the process, highlight problems and opportunities, and keep leaders focused on their daily activities.

Maturing to Lean as a Philosophy

We're not done yet. We've covered the Lean tools as taught in class and now understand the tools of Leader Standard Work. But one more component still needs to be in place to truly and fully become a Lean enterprise. As mentioned above, the rules of the Gemba walk give us a glimpse into a true Lean leader's most basic behavior and attitude: ask why and show respect.

Traditionally, when you're promoted to a position of leadership, you are given a "grant of authority" over a function or area of the organization. You're the boss and get to boss "your people" around. Flip that on its head for a Lean leader. Once promoted into a leadership position, you are given a "grant of responsibility" over a function or area, and it is your responsibility to pull the very best you can from that area of responsibility. The physical mechanisms of Lean, pull systems, etc., reflect the philosophy of Lean: pull the very best out of the organization by asking why, with respect.

Asking why is hard work. It's so much easier to say "do that" or "don't do that". Those are simple commands that leave no room for discussion or learning. Asking why we did something or if we can do something is the start of a conversation. It's the start of a conversation where the leader can learn more about the process, and those working in The Gemba can gain a deeper understanding of their own process by explaining it to others. It's the start of a conversation that asks questions about why something happened, how we can improve it, and how much more we can do.

Again, thinking about the right questions to ask and pulling the very best out of everyone within our realm of responsibility is hard work. Very hard work. It takes preparation and a willingness to be patient and learn. I can simply tell my kids how to do a math problem -- that's easy -- or I can work hard to think of examples to connect the math concept back to their frame of reference, to pull that understanding through them. That is asking why. That is showing respect for them and their experiences and putting the burden on the leader to pull the team to the best possible outcome. That's hard work, especially at 11:00 pm on a school night.

In Lean, we say we need to "go slow to go fast." Going slow means having the patience to understand: to understand who your customer is and what their needs are, to understand the root causes of problems, to understand all of the possibilities and opportunities for improvement, and to pull all of that understanding together into the best possible solution. And then to recognize that solution as an experiment, not a commitment—an experiment that we will learn from, refine, and repeat tomorrow.

Embracing Questions Over Answers as a Lean Leader

As soon as we understand that Lean (and life) are a series of experiences that we can and need to learn from, we open the door to continuous learning and improvement. And that lesson is the hardest to learn as a leader who has made it to the top by having all the right answers. Recognizing the need to transition from being the one with all the answers to being the one with all the questions—that's the secret of a Lean leader and a lean transformation.

Did Toyota risk much by inviting any and all to come and see how they did things in their Georgetown, Kentucky plant? Probably not. Or we can probably strengthen that statement to definitely not. Yes, the tools of Lean would be on display: kanban cards moving about managing the flow of just-in-time inventory, huddle boards and metrics showing the state of the process, and visual signals everywhere showing where everything is going to flow. The five principles of Lean would be on display and easy to see. Even the tools of leader standard work might be on display for all to see. But the philosophy of the Lean leader and the hard work of asking why and showing respect, while certainly on display, is much harder to see. Especially for those that aren't looking.

MoreSteam Client Services

Dr. Lars Maaseidvaag continues to expand the breadth and depth of the MoreSteam curriculum by integrating the learning of Lean tools and concepts with advanced process modeling methods. Lars led the development of Process Playground, a Web-based discrete event simulation program. Before coming to MoreSteam in 2009, he was the Curriculum Director for Accenture/George Group and has also worked in operations research and management consulting.

Lars received a PhD in Operations Research from the Illinois Institute of Technology. Prior to his PhD, Lars earned a M.S. in Operations Research and Industrial Engineering as well as an MBA from The University of Texas in Austin.