Lean Roadmap

Lean Roadmap - Sense out of Alphabet Soup

One of the questions that we are most frequently asked is: "How do we possibly make sense out of all the alphabet soup of programs and techniques for continuous improvement - Lean, TQM, JIT, Six-Sigma, TPM, Kaizen, SPC, BPR?"

The central mission of the Lean Enterprise Resource Center is to help you cut through the confusion. The first step is to understand the root cause of program complexity.

Much of the diversity of program names and acronyms arises from the importation of unfamiliar Japanese concepts. However, beyond that factor, many programs are promoted and supported by individuals or firms with an economic interest in their adoption. On some occasions, collections of activities are given names and acronyms for marketing purposes - either internally or externally.

As a result, claims are made that a given program is the overarching "mother-of-all-continuous improvement programs". We have certainly seen this with Six Sigma, BPR (Business Process Re-engineering), and TQM. We believe that a new synthesis of programs would be useful to combine the best features under one initiative.

Where to start?

As a starting point, it is important to recognize that many of the underlying fundamental problem solving tools and techniques are shared.

For example, virtually all improvement programs use team-oriented problem solving techniques like pareto analysis, cause and effect charts, trend charts, and brainstorming. At the core, most process improvement programs represent a structured, team-oriented application of the scientific method to find and fix the root cause.

Secondly, none of the programs or methods work at cross-purposes - they are all mutually supportive.

For example, TPM small group activities to improve equipment reliability go hand-in-hand with higher-level Six Sigma initiatives to reduce defects because failing equipment often produces defects as well as production downtime.

Likewise, Six Sigma efforts to improve the manufacturability of a product may reduce equipment complexity, therefore indirectly improving the uptime of the production facility. The TPM and Six Sigma programs are not mutually exclusive, they are mutually supportive. They draw on many of the same basic problem-solving skills.

Lean Enterprise - A Framework for Integration

The MoreSteam.com approach to process improvement is to identify the fundamental activities that add value and develop a framework to apply those activities in a systematic fashion - irrespective of program acronyms.

If you are familiar with the work of W. Edwards Deming, you know that he didn't proliferate acronyms by inventing names for his ideas on continuous improvement - he focused on the activities themselves.

This is not to say that names and acronyms are not valuable - they are. A common language is critical to process improvement. The missing element is an understanding of the overall framework of how all of these programs inter-relate, and in many cases, overlap.

We believe that Lean Enterprise is the best top-level framework to organize process improvement activities because it has a broad and simple definition based on providing value (satisfaction) to customers.

The Lean Enterprise

The Lean Enterprise is defined as an organization that creates customer value through a process that systematically minimizes all forms of waste. Forms of waste include: wasted capital (inventory), wasted material (scrap), wasted time (cycle time), wasted human effort (inefficiency, rework), wasted energy (energy inefficiency), and wasted environmental resources (pollution).

A firm can achieve Six Sigma process capability and not be Lean, but a firm cannot be Lean without achieving high process capability. Likewise, a firm can have high equipment reliability from an effective TPM program and not be Lean, but a firm cannot be Lean without high equipment reliability.

Lean Enterprise is the best description of the overarching goal to be achieved through application of various process improvement methodologies - and is a critical concept to make sense out of the alphabet soup of programs and techniques. Without a synthesis of program objectives and activities within an overall framework, organizations can suffer death from a thousand initiatives.

Likewise, the singular adoption of one program often does not provide a broad enough collection of activities to propel broad, sustained improvement in business performance. This strikes at the second question frequently asked by business leaders: "Why do so many improvement programs fail?"

Why Do Process Improvement Programs Fail?

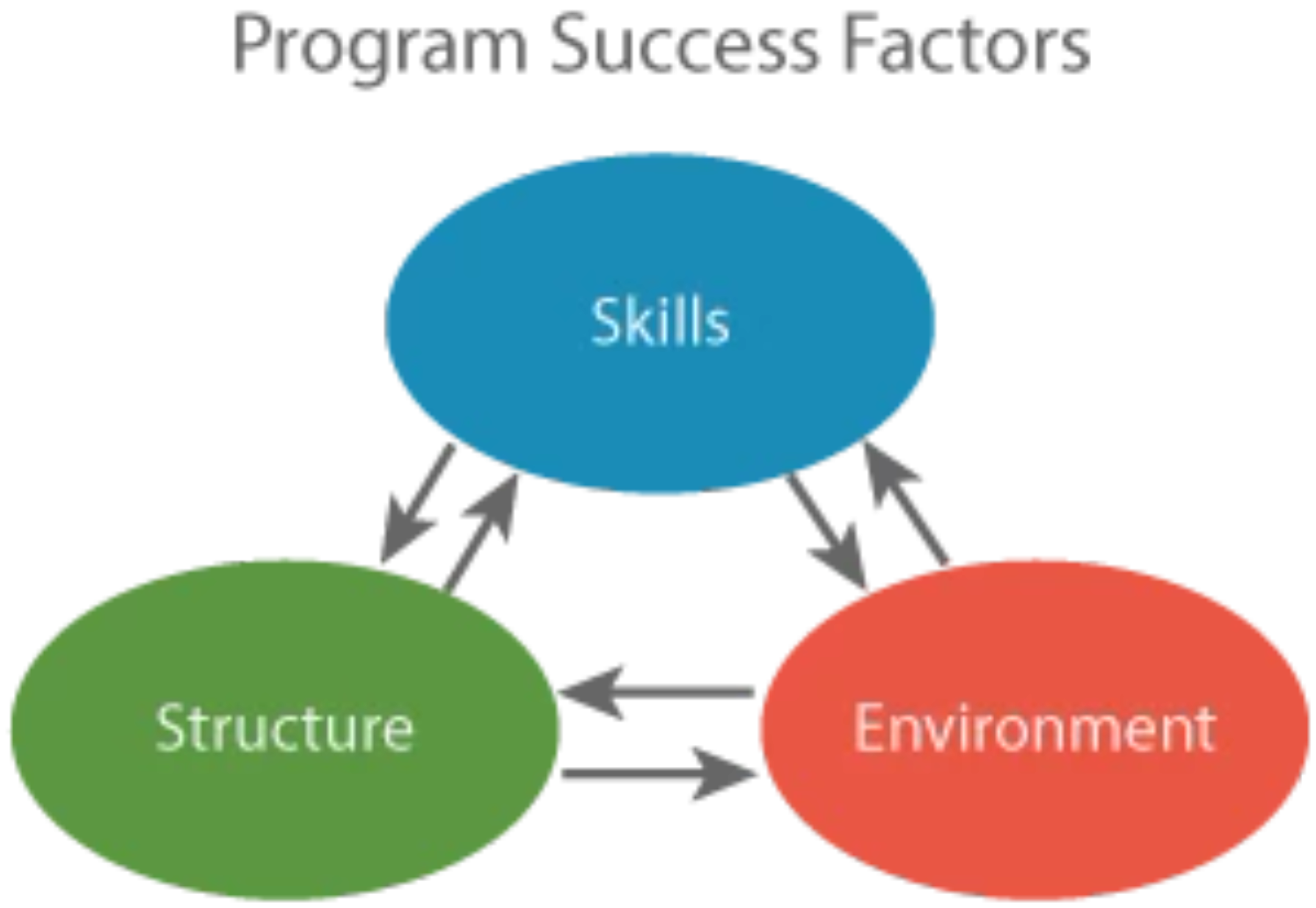

Consider the simple model below (Figure 1) to describe the most basic elements of successful process improvement efforts:

Successful program implementation depends upon three basic inter-related factors, which must be present consistently over time:

Skills

The organization must be broadly educated to apply the right collection of process improvement tools. Many tools are needed to build a house, and all are necessary for the overall effort to succeed. A good saw does not compensate for a missing hammer.

Beyond identifying the tools that are required, building the organization toolbox requires a means to deliver education content as needed, as well as the basic capability to learn, master, and apply that content.

Structure

Skills are of diminished usefulness without a systematic structure to prioritize and guide their application on a broad scale. Efforts must be focused on the business issues that translate into customer value and waste elimination.

Process improvement must cross organization functional boundaries, and can cause functional frictions (e.g. manufacturing vs. engineering), usually because of inappropriate performance metrics. A rigid functional organization can squelch cross-functional improvement efforts that inevitably require trade-offs.

In recognition of this, many firms are reorganizing around processes rather than functions. The successful implementation of Lean practices requires a Value Stream Manager who owns the value stream across functional boundaries.

Environment

The workforce must be motivated and engaged to apply the skills within the structure. Recognition, compensation policies, and the business culture must consistently support team oriented process improvement or it will die.

The workforce must understand WHY it is important to improve processes, and feel that they have a meaningful stake in the success of those efforts. A systems perspective is necessary to connect cause and effect and therefore fully understand the WHY of Lean Enterprise thinking.

Programs fail because of a weakness in one of these three areas. A basketball coach once said that "it doesn't do any good to steal the ball and then dribble it off your foot!" The message is that any program requires all of the important elements to be present.

Process improvement is an organic process. Think of it like tending a garden, which relies upon the correct application of several mutually supportive activities - good soil, sunlight, water, fertilizer, pest control, pruning, etc. All of those activities can represent process improvement programs. All are important, but the garden doesn't flourish unless several of them are present in the right mix over time.

Core Activities of the Lean Enterprise

Programs fail because of a weakness in one of these three areas described above. A basketball coach once said that "it doesn't do any good to steal the ball and then dribble it off your foot!" The message is that any program requires all of the important elements to be present.

In his book The Fifth Discipline - The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization, Peter Senge points out that economically viable commercial aviation did not arise until a full 31 years after the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk because the development of five separate component technologies was necessary to achieve the required aircraft performance characteristics.

Retractable landing gear, variable pitch propellers, radial air-cooled engines, light-weight body construction techniques, and wing flaps were not combined for the first time until the DC-3 - enabling the first successful commercial aircraft. None of these technologies was sufficient in isolation - development of commercial air travel required a synthesis of all five developments.

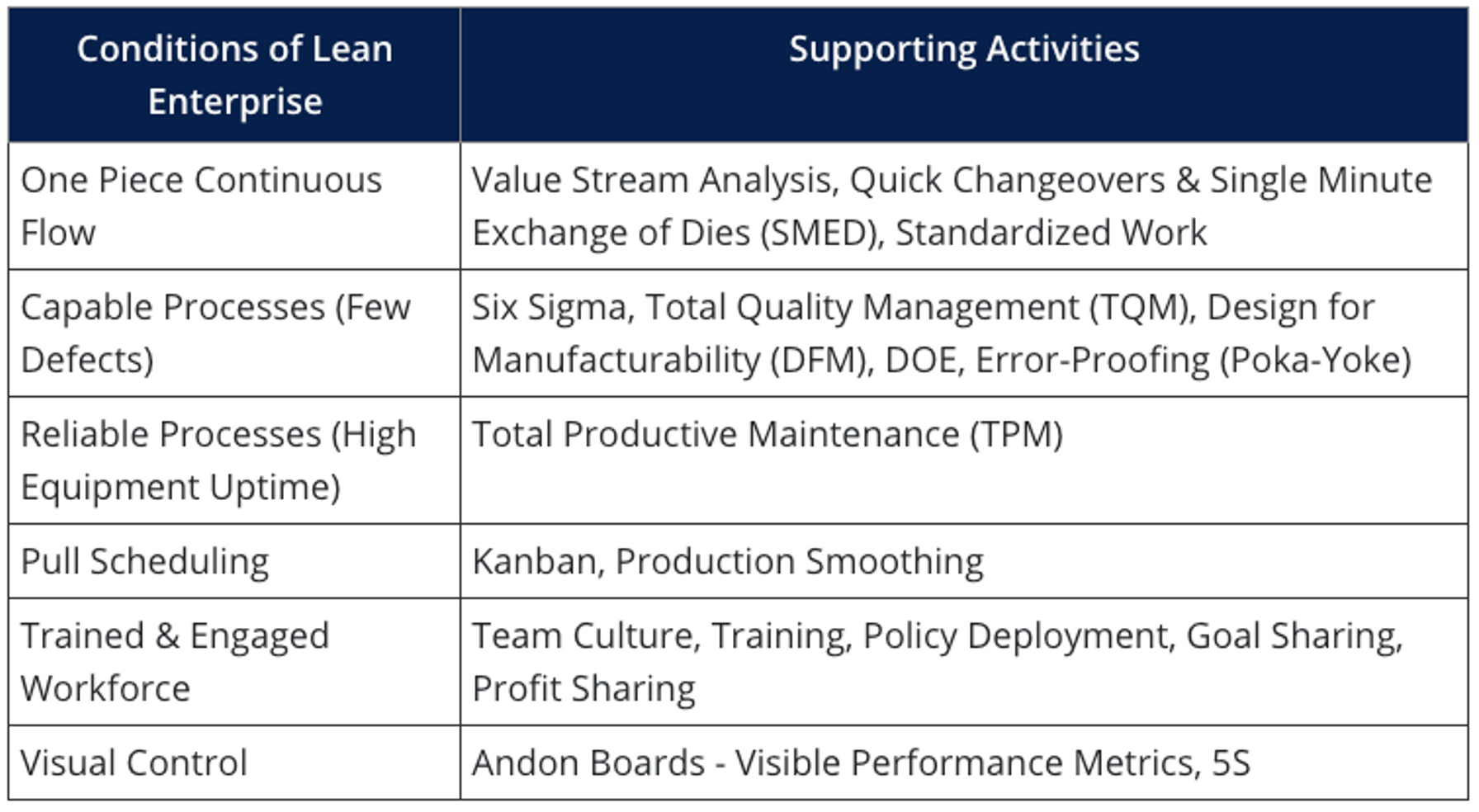

In the same vein, the Lean Enterprise relies upon a synthesis of multiple interdependent process improvement methods and techniques. To clarify the Lean picture, separate the conditions or components that define a Lean Enterprise from the activities that generate those conditions:

The supporting activities are in turn characterized by the Skills, Structure, and Environment model as previously discussed.

Another way to think about the Lean Enterprise goal is to move from reaction to specific Events to managing Systems, and ultimately to cultivating stakeholder Mental Models and Behaviors (see the System Dynamics tutorial in the MoreSteam.com Toolbox for further discussion on this point).

This is the human equivalent to moving up-stream in the design process where the leverage is greatest to improve cost and quality. Many programs focus on managing events rather than systems and mental models, and that is one reason why they ultimately fail.

The collection of integrated and mutually supportive Lean enterprise activities can be compared to a nuclear reaction: if there is enough activity and proximity, the right material will feed off itself in a sustained chain reaction. Unfortunately, it is not quite that simple, but the metaphor does offer some resemblance to the organic nature of a functioning Lean system.

The Lean Enterprise and Six Sigma

Six Sigma is a method to make processes more capable of not producing defects. A Lean operation depends upon capable processes. Defects are a major source of waste - internally as rework and scrap, and externally as warranty and/or customer dissatisfaction. Lean enterprises also use other process improvement methods, namely TPM (single point lessons) and Kaizen activities.

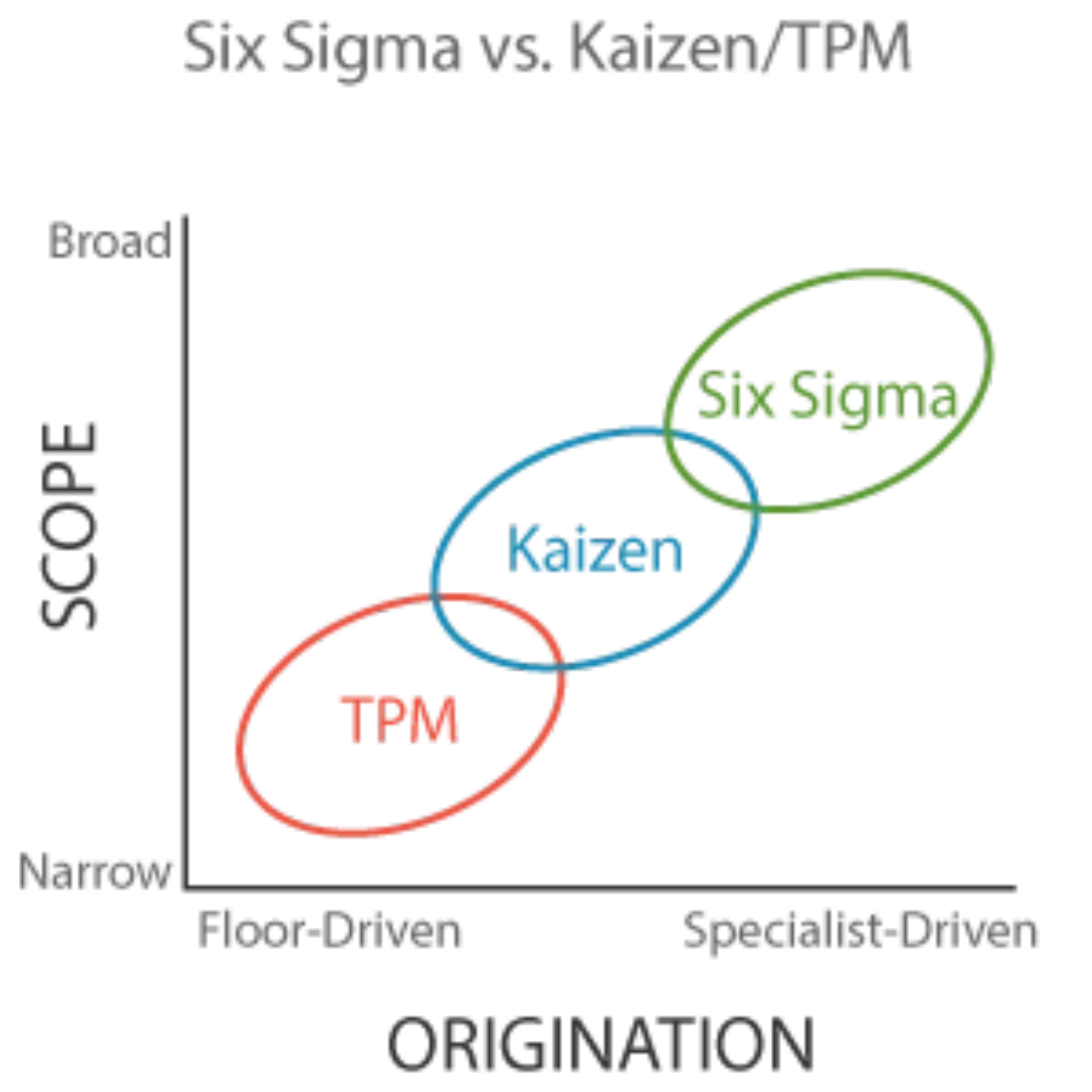

In general, all three activities have a common denominator of problem solving tools - pareto charts, trend charts, 5-why analysis, brainstorming, etc. A primary difference is the scope of problems/processes addressed, and the origination of the effort, as shown by Figure 2.

At one end of the spectrum, TPM activities tend to be driven from small teams on the production floor on a daily basis. Kaizen events are used to support TPM, but are larger in scope, and may have more involvement from staff specialists. Six Sigma programs are driven by trained specialists - "Black Belts" - who do not also have line responsibility.

Note that this discussion is very general. Some organizations have extended the scope of their TPM activities well beyond equipment effectiveness to encompass employee safety, overall product quality, and cost reduction. Likewise, Six Sigma programs have been extended to encompass narrower shop floor issues.

Leading to Lean

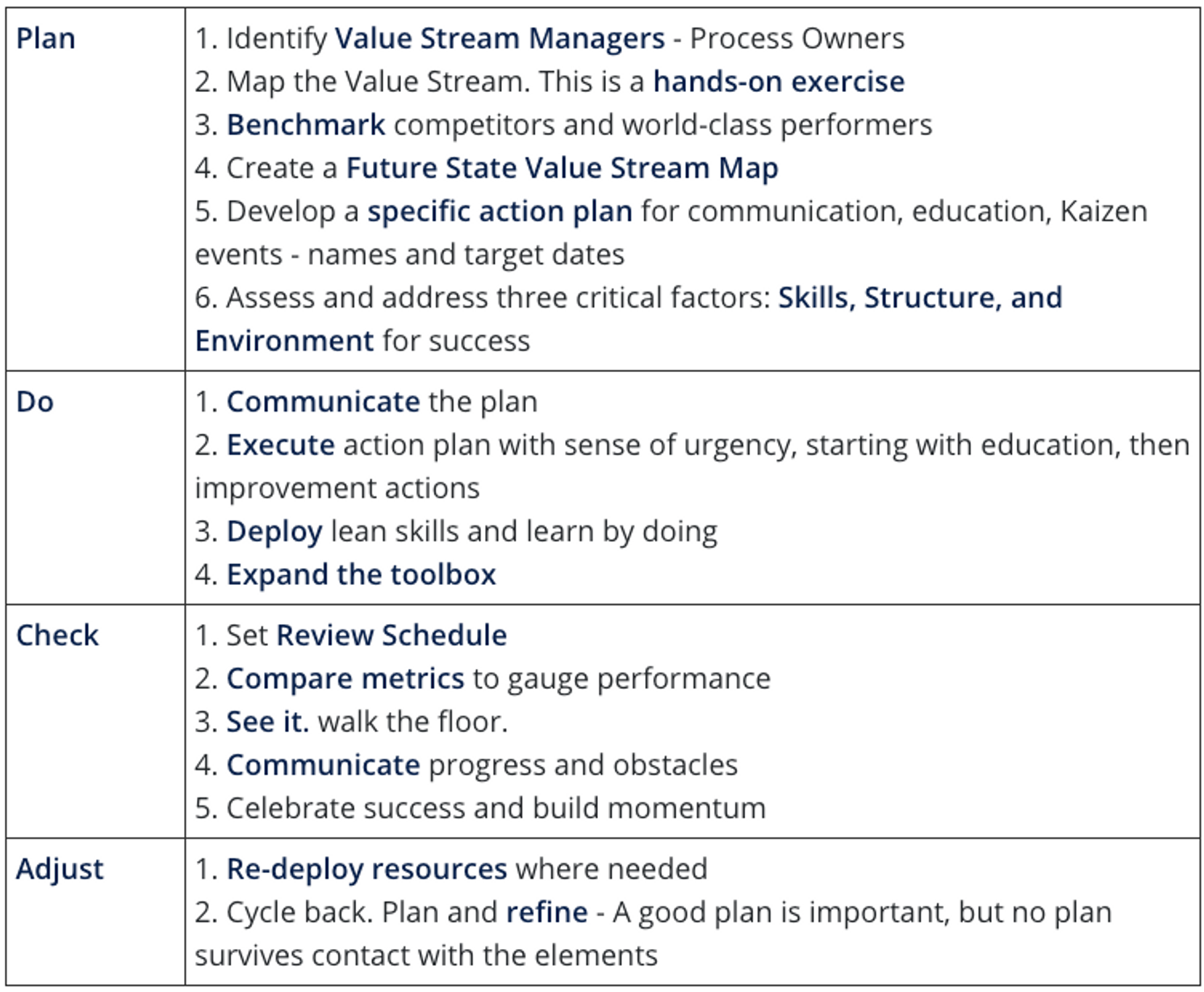

The process toward becoming a Lean Enterprise proceeds on three levels through a similar sequence of activities following the Plan-Do-Check-Adjust cycle.

The first level is strategic, or company-wide. The second level is plant or location oriented. The third level is process-specific within a location.

At each level, an important activity to facilitate planning is to define the current condition with data - establish a measurable baseline for improvement. A high level value-added flow chart is a good place to start (see Value Stream Analysis). The value-added analysis identifies priority improvement areas and provides a common language to focus activity.

As you cycle through the P-D-C-A process, move to deploy throughout the organization and integrate activities across functional boundaries while continually raising the performance bar.

Recommended Books

- James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones. Lean Thinking (1996, Simon & Schuster) ISBN 0-684-81035-2