New Perspectives on the Seven Basic Tools of Quality

Back in the 1950s, quality pioneer W. Edward Deming emphasized basic tools for quality improvement. Inspired by Deming's lectures in Japan, Kaoru Ishikawa is attributed with a further refinement of Deming's basic tools into seven specific tools:

- Cause and Effect Diagrams

- Check sheets

- Control (Run) Charts

- Stratification

- Histograms

- Pareto Charts

- Scatter Plots

Ishikawa believed that "As much as 95% of quality related problems in the factory can be solved with seven fundamental quantitative tools". This group of tools was touted as simplifying the perceived complexity of continuous improvement, thus bringing a quality focus to front‐line employees.

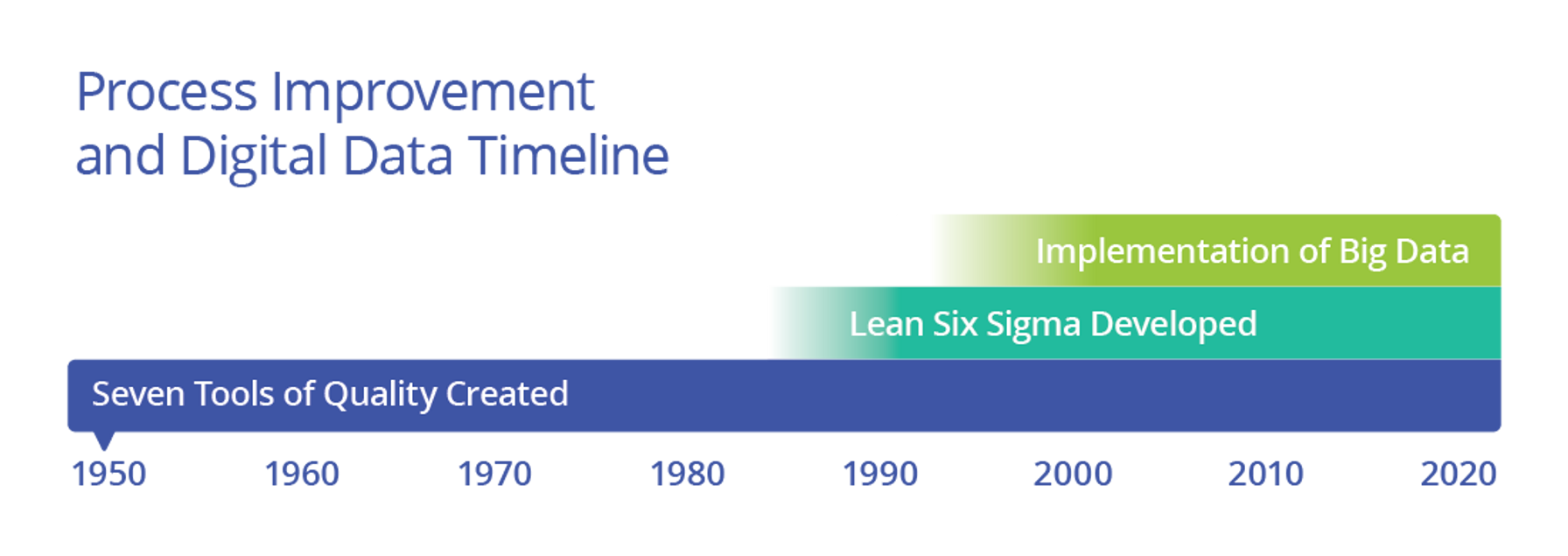

But that was almost 70 years ago, and much has changed in the interim. Quality improvement is now a thoroughly digital activity (Quality 4.0).

It's worth examining whether Ishikawa's belief has held true in modern application. Are companies successfully using these seven tools to actually solve 95% of their quality problems? Are these the right tools? Is anything missing? And if so, what is a good model going forward?

If these simple tools are so powerful — sufficient to solve 95% of all quality problems — then most of our existing quality problems should have been solved already. It sure doesn't feel that way. Something must be missing from the equation.

It could be that the simple tools are not being employed correctly, or not employed at all, or that some problems require more complex solutions using different tools, or that any of the innumerable other inputs to the improvement process are lacking. Or perhaps new problems are created so quickly that there is no way to keep up. The answer is probably some combination of all of these explanations. That's a lot to take on, so focusing on the problems that do get solved, let's start with the question of which quality improvement tools are actually used most frequently.

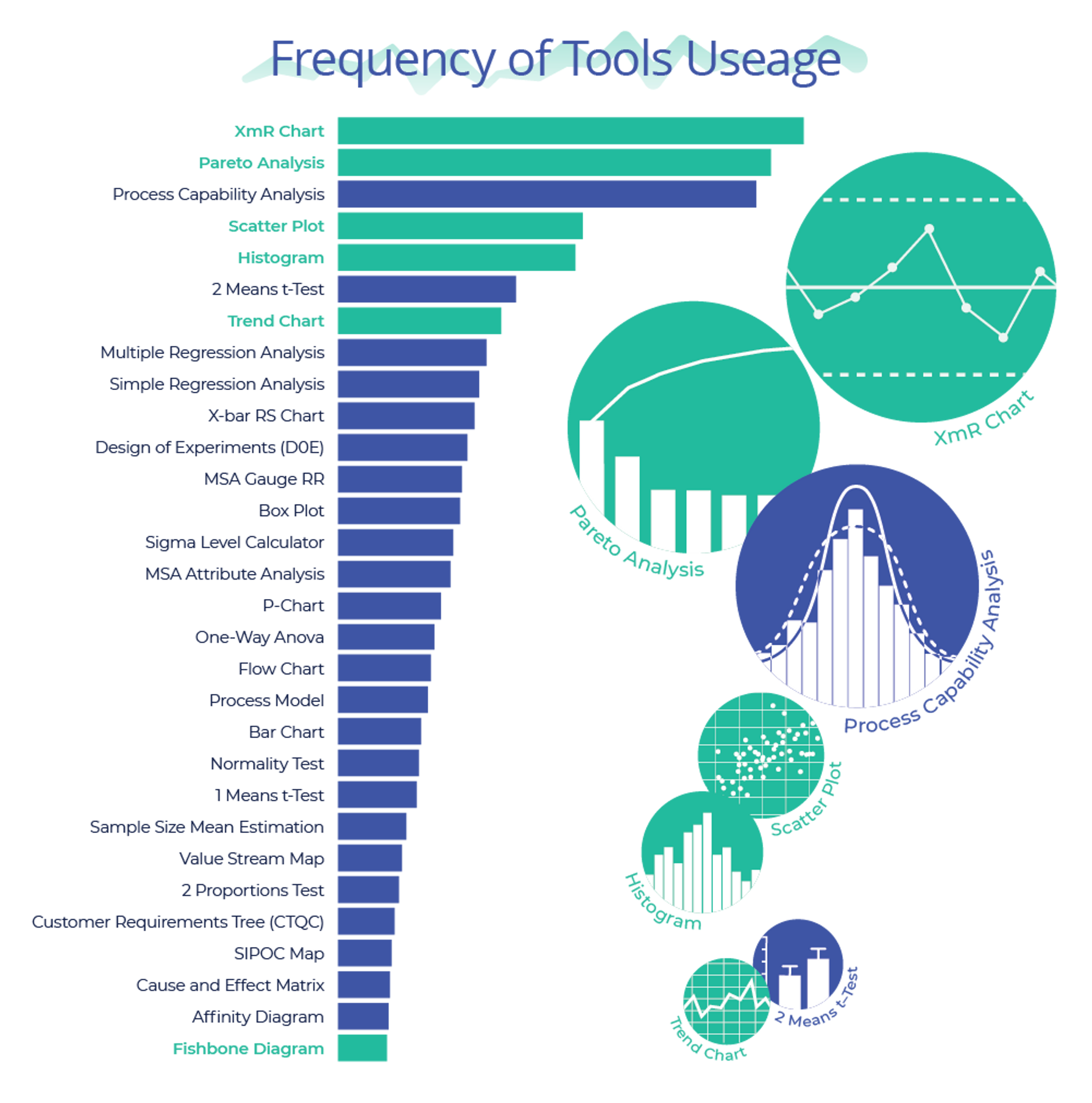

Fortunately, we don't have to guess about the use of tools because MoreSteam's EngineRoom problem-solving application keeps track of tool usage. We can sample actual practice to get a picture of relative tool usage frequency. It's not a perfect picture because some practitioners may use certain tools without the aid of software. For example, process maps can be drawn on a whiteboard and other tools can be employed by hand. But with that caveat, let's see what we might learn from the data. It seems only fair to use analytics to better understand the use of analytics!

Here's a pareto chart of tool usage representing several thousand quality professionals. The 7 Tools of Quality are highlighted in green, and true to form, they show up in five of the top seven spots. It's really quite remarkable that those tools have been so persistently useful over time. The core of Ishikawa's assertion appears to be true. But there are many other tools beyond the subset of 7 that are used with great frequency.

It's worth examining whether Ishikawa's belief has held true in modern application. Are companies successfully using these seven tools to actually solve 95% of their quality problems? Are these the right tools? Is anything missing? And if so, what is a good model going forward?

If these simple tools are so powerful — sufficient to solve 95% of all quality problems — then most of our existing quality problems should have been solved already. It sure doesn't feel that way. Something must be missing from the equation.

It could be that the simple tools are not being employed correctly, or not employed at all, or it could be that some problems require more complex solutions using different tools, or that any of the innumerable other inputs to the improvement process are lacking. Or perhaps new problems are being created so quickly that there is no way to keep up. The answer is probably some combination of all of these explanations. That's a lot to take on, so focusing on the problems that DO get solved, let's start with the question of which quality improvement tools are actually used most frequently.

- Considering that these tools were originally selected for a manufacturing environment, are they universally applicable across industries, including service businesses?

- Are the people using these tools being successful with just these tools?

- Is this list sufficient to implement and sustain improvement?

- If not, what's missing from the list?

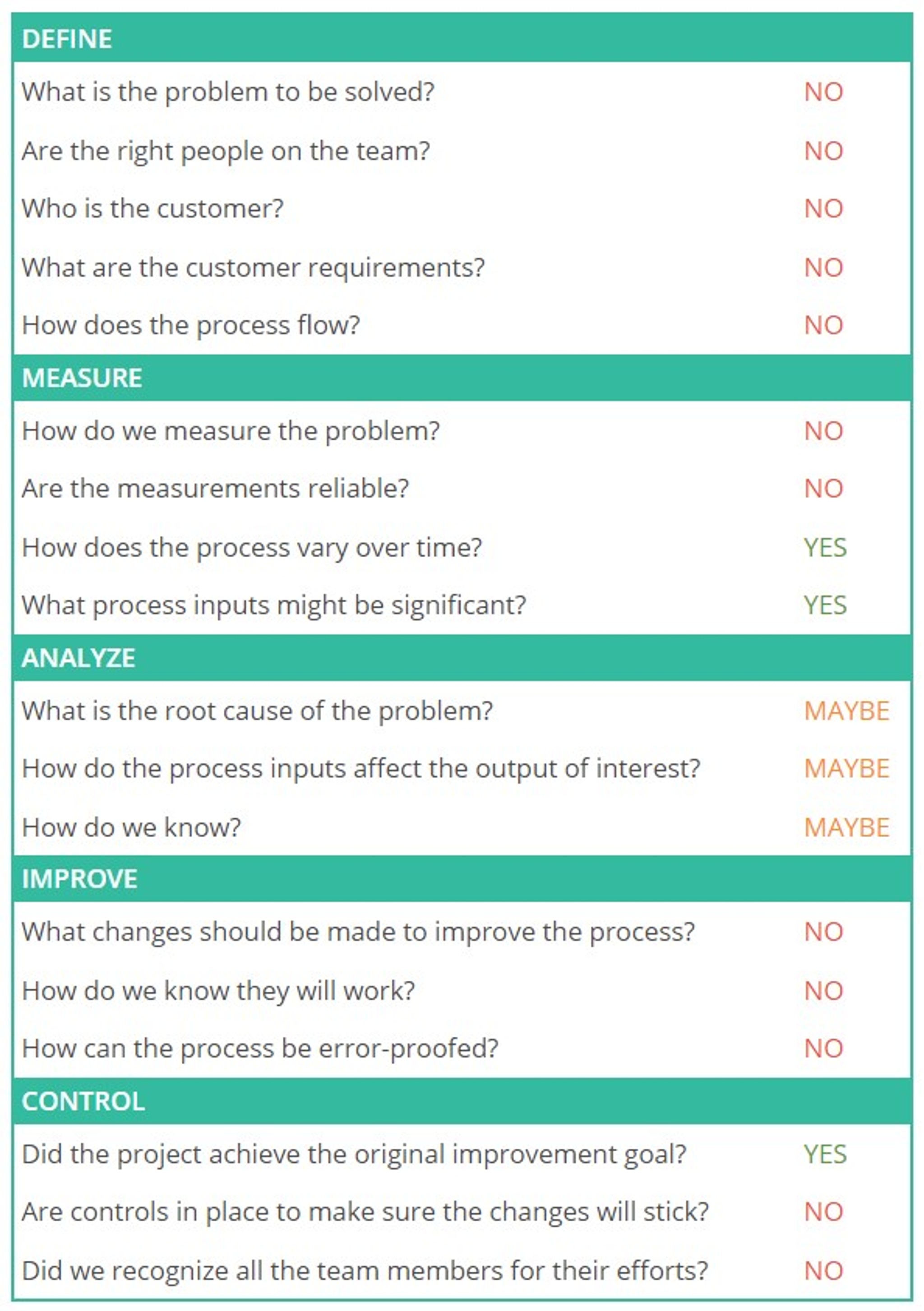

One approach to answering these questions is to review the critical questions that must be answered when working through the Lean Six Sigma DMAIC process, and determine whether the seven tools would likely be sufficient to answer the questions.

The high-level critical questions are shown below, by phase of DMAIC, along with an assessment of the ability of the 7 Tools to answer the critical questions that drive improvement.

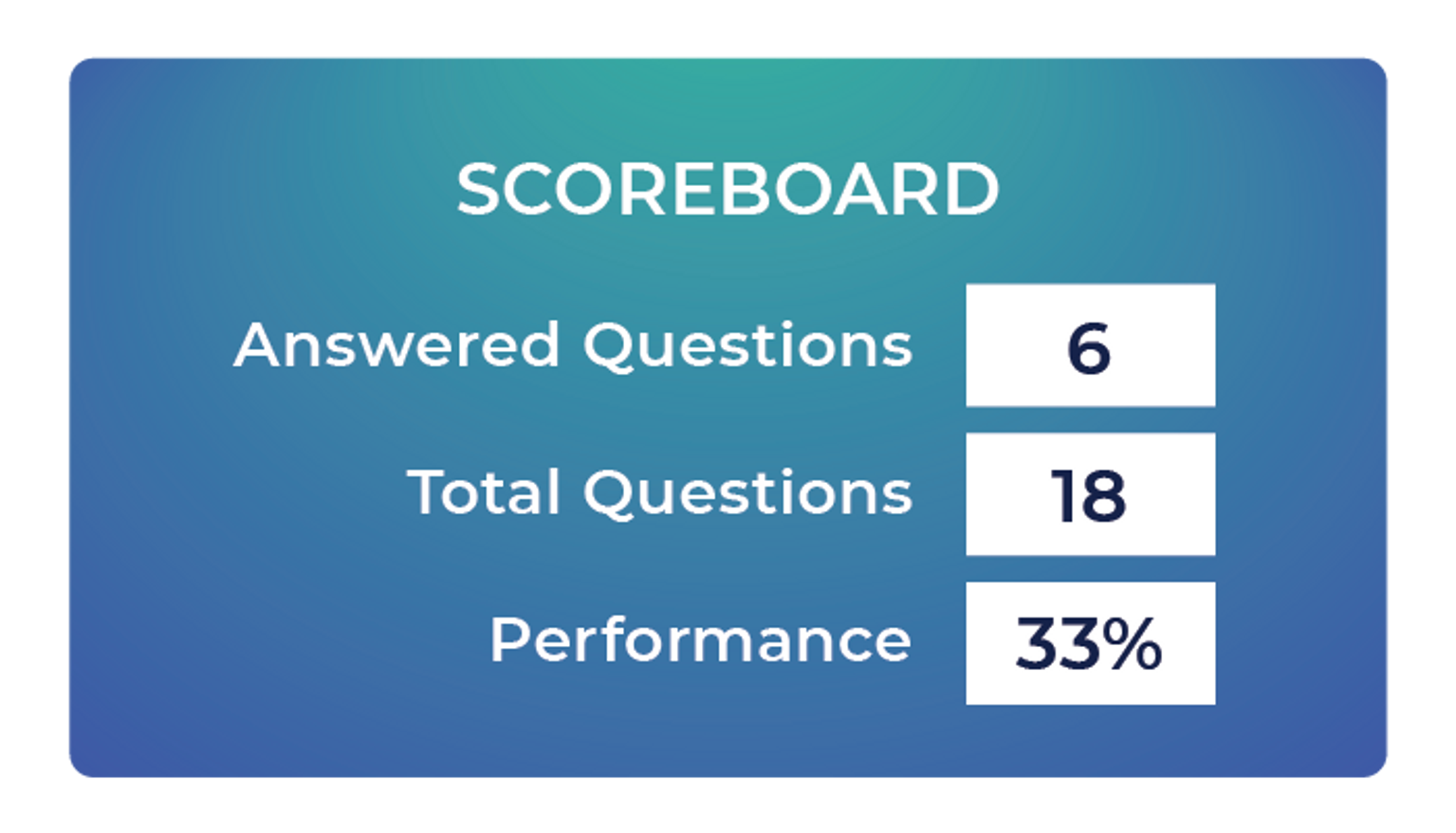

If we count the "Maybes" as "Yesses", that makes 6 questions answered out of 18, or 33%, far short of world-class quality standards!

The "7 Basic Tools" are powerful but too basic to fully resolve many problems. Some of the obvious gaps include tools to collect and analyze customer requirements (VOC), tools to understand process flow, tools to evaluate measurement systems, tools to investigate causal relationships, and tools to implement and sustain improvements.

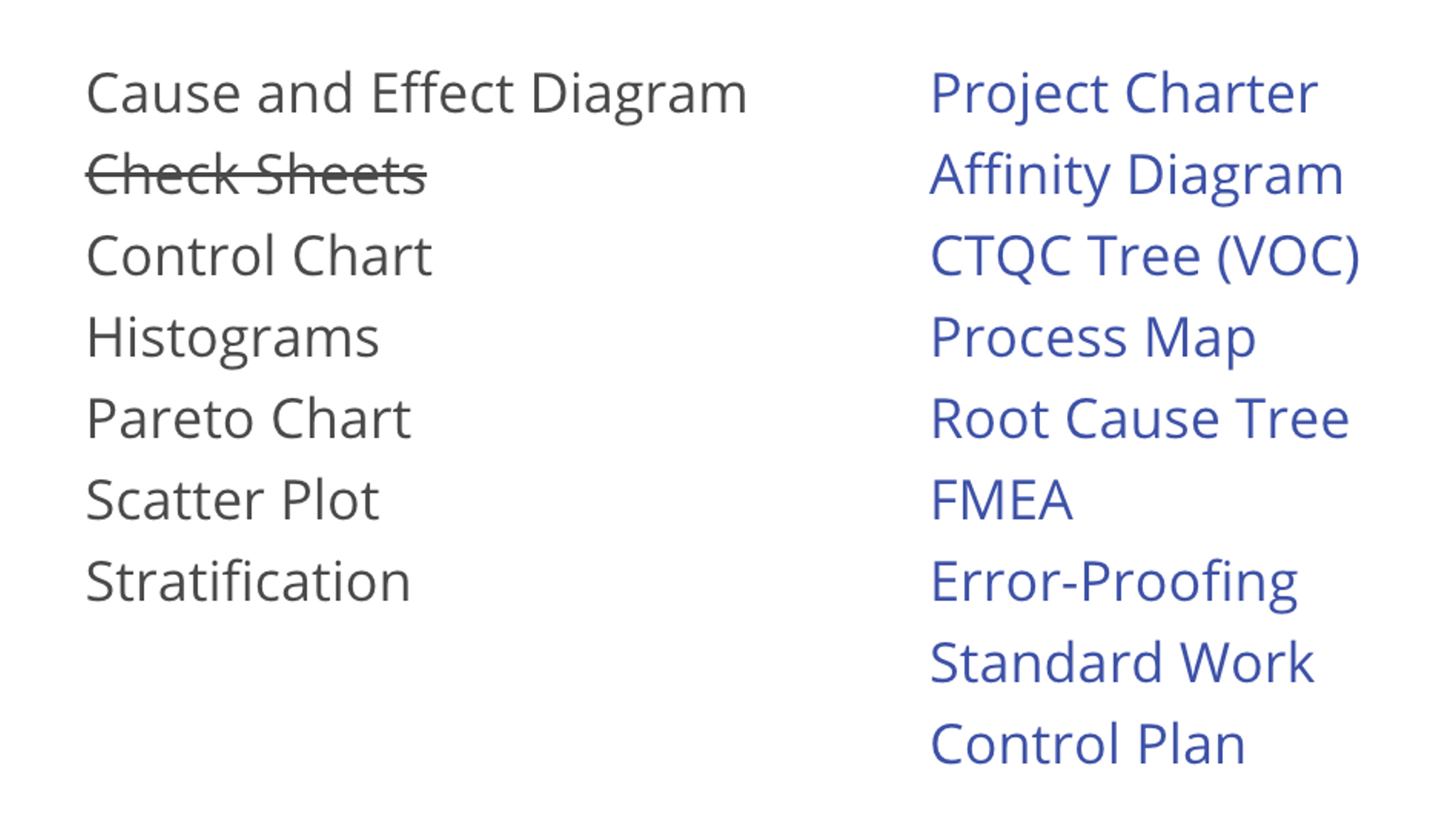

To close the gap, here's my updated list, which drops Check Sheets (manual data collection is no longer common) and adds 9 other tools, for a total of 15. It's still a "vital few" subset of the larger universe of quality improvement tools:

With this revised list of tools, a review of the critical questions listed above shows that virtually all of the critical questions can be answered on most quality improvement projects.

Would that do it? Is anything missing? This analysis of tools is actually a pretty narrow view of process improvement. I would argue that these tools, while necessary, are insufficient to operate a quality improvement system. Even a tool that is simple and powerful must be used in order to reap a benefit. Returning to the issue of "if these tools are so great, why aren't all the problems solved?," there are apparently other inputs that may be worthy of greater attention. It's not that tools aren't important, they are, but there is just so much more involved in solving difficult problems.

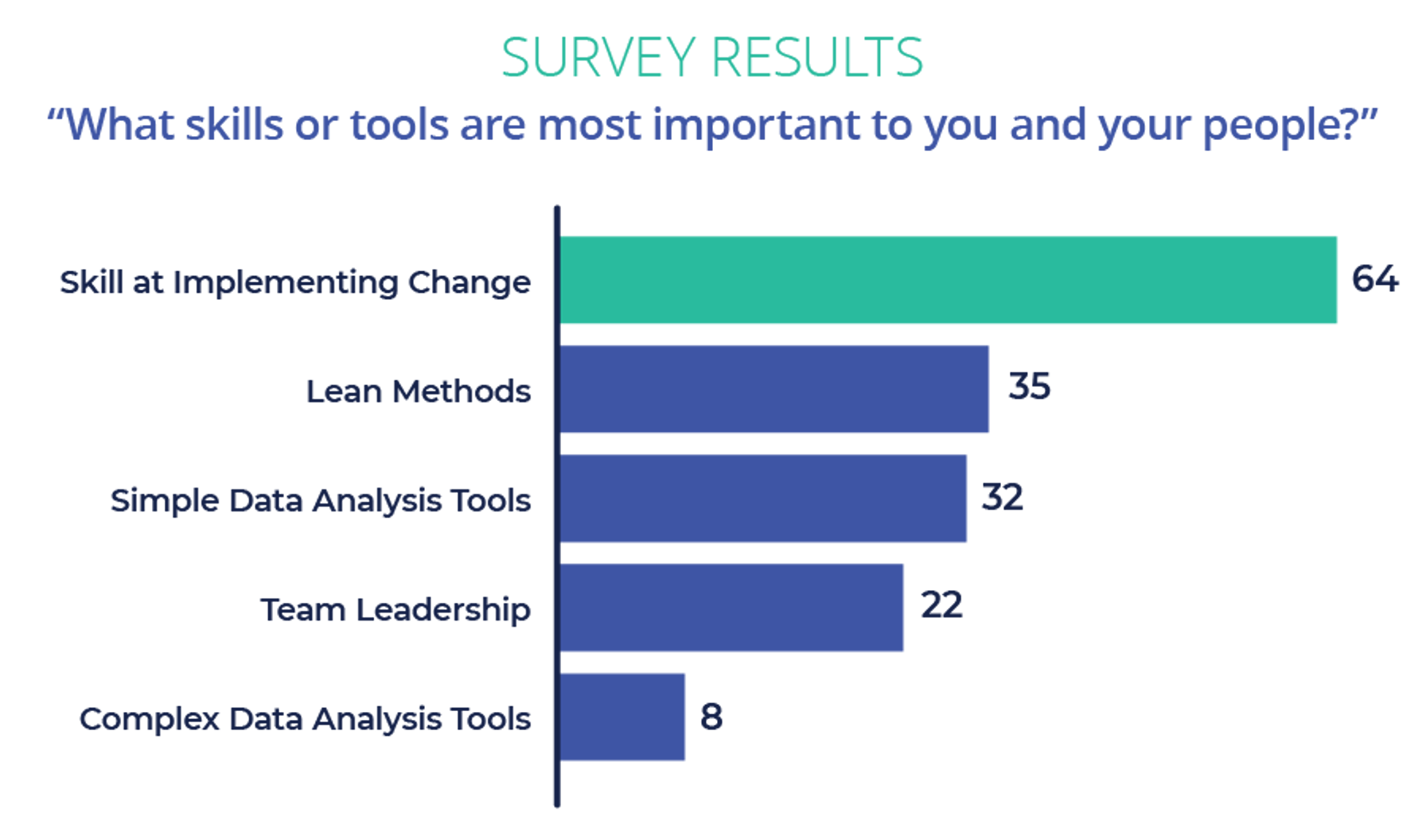

A recent survey of process improvement leaders posed this question: "What skills or tools are most important to you and your people?" Their responses are shown below, and It's pretty clear that the soft skill of implementing change in an organization of people is by far the most important capability gap to close.

Working with people to implement change is probably much more difficult than using the data tools, because as challenging as it may be to work with data, convincing people to do something they don't really want to do is a lot harder. Process improvement is a contact sport, and without the soft skills necessary to work effectively with other people, all conversation about quality tools, basic or otherwise, is largely irrelevant.

So soft skills are important. What else?

In many ways, what we call "soft" skills are expressions of personal attributes. So here's another perspective: maybe the most important "basic seven tools" are really not tools at all, they are personal attributes. Here are a few that stand out to me:

- Persistence

- Courage

- Honesty

- Persuasiveness

- Curiosity

- Patience

- Sincerity

In the absence of these attributes, soft skills can't be developed, and the basic tools, whether 7 or 15, are worthless.

Basic problem‐solving tools and positive personal attributes that translate into soft skills both seem to be critical inputs to effective process improvement, but these components are often not enough. We've all seen situations where effective people using the right tools were not able to effect meaningful process change.

Quality Improvement is only effective when it's part of a system — a structure that identifies the right problems to solve and provides leadership support of the necessary work. If that robust structure is in place, then yes, the application of tools by capable motivated people may be enough, but it's not something to be taken for granted. It's a dynamic system that is constantly stressed, so it requires ongoing maintenance, repairs, and adjustment. That is the role of leader standard work, designed to reinforce the productive habits necessary for system stability and performance.

The Broader System

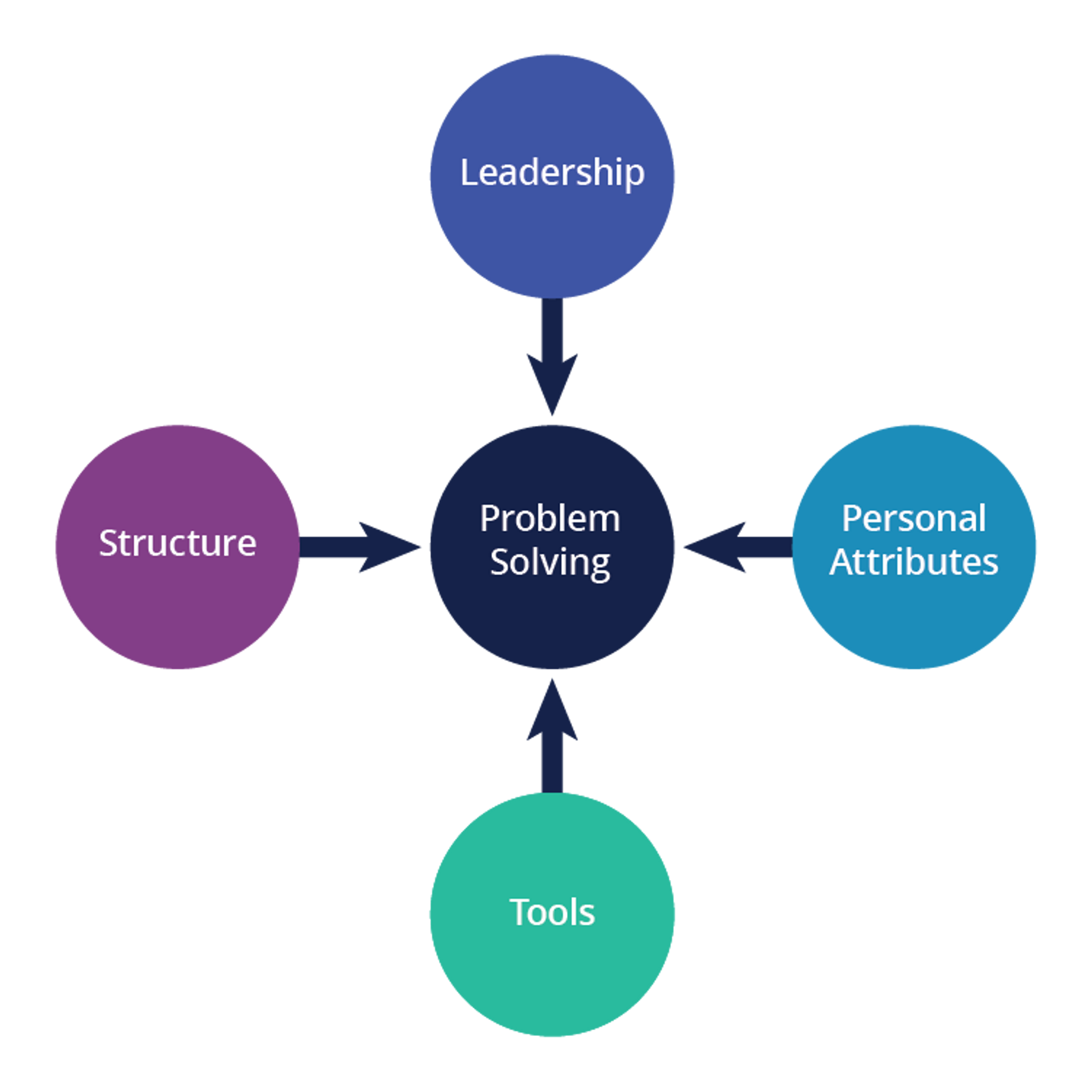

Let's expand our model to include the organization's problem‐solving structure and the leadership behaviors that build and support that structure. The model below shows four primary inputs to problem‐solving, representing a more comprehensive system designed to be durable and sustainable.

I've added Leadership and Management Structure. Leadership engagement and support is crucial to effective organizational problem‐solving, and equally important to provide a consistent sense of the "true north" of the organization. Otherwise, it's easy to work on problems that don't actually align with the organization's strategic imperatives. "Structure" represents daily management systems that guide and support the people doing the work of problem‐solving, as well as the digital information structures that provide relevant and timely information (data) necessary to undertake scientific problem‐solving.

This model provides more perspective and context to the role of tools. Tools are essential, but they are only effective in the right hands, in the right structure (management system), and with the right support and alignment to organizational imperatives (leadership).

In my experience, people who effectively lead teams are never stymied because they don't have an analytical tool at their disposal. Those team leaders know how to formulate the right questions to guide their analysis, and they can always get help with any given tool if needed because they have good interpersonal skills and persistence. That's why tools are shown at the bottom of the diagram above.

The Secret Sauce

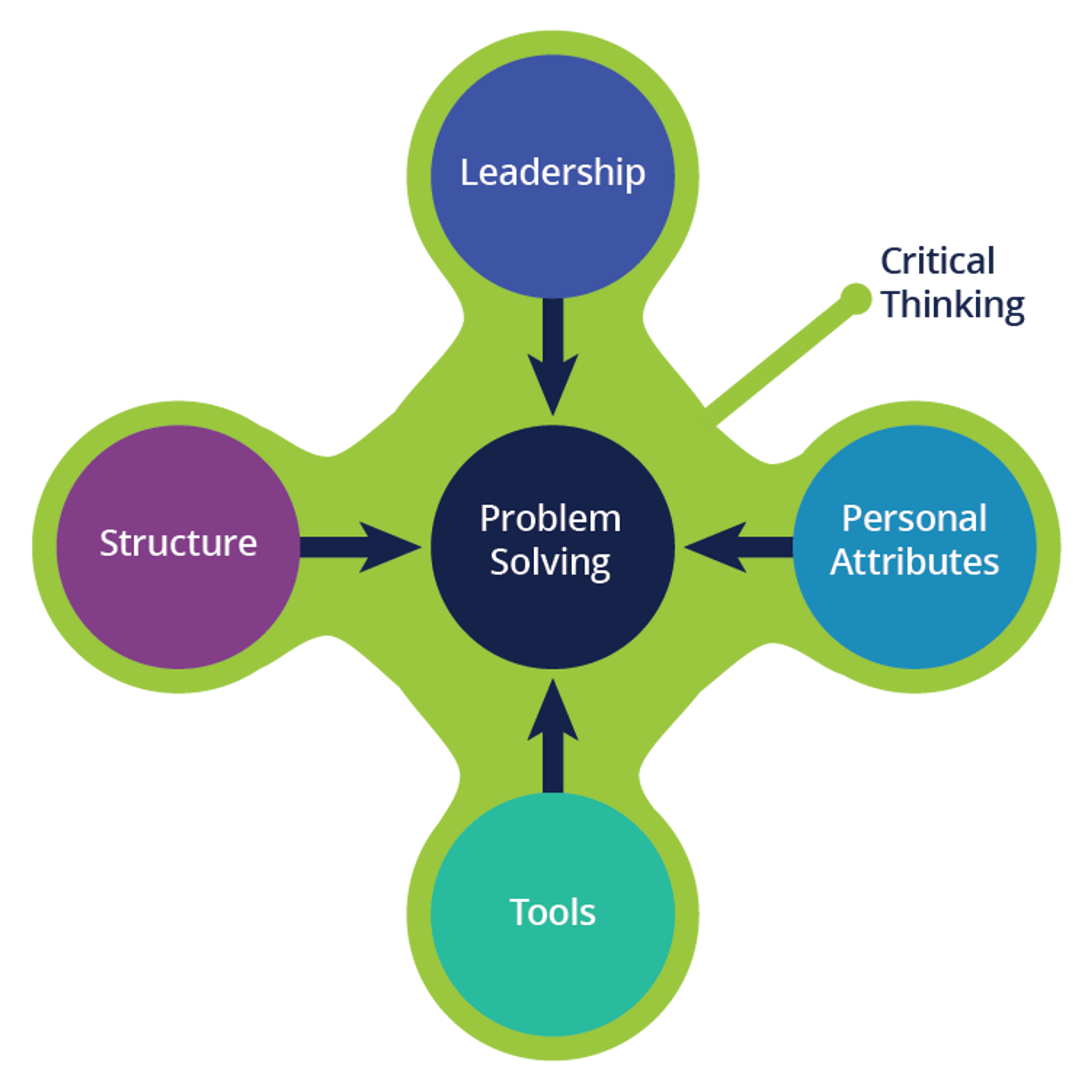

Formulating the right questions is a prerequisite to the use of all quality tools, and answering those questions requires further critical thinking to guide investigation and inform interpretation. That question‐action‐answer sequence has tool usage in the middle, but it is driven from start to finish by critical thinking. A singular focus on tools gives short shrift to the thought process at the heart of any effective problem‐solving system. In fact, I would argue that skillfully applied critical thinking is a sort of glue‐catalyst secret sauce that holds the whole system together while driving it forward.

In this expanded model, critical thinking is a culture of good habits of data‐driven decision‐making that infuses all of the other system components, binds them together, and drives the model forward to recognize and solve problems (get results). With that last element in place, the system is complete, robust, and sustainable.

Summary

We've seen that the classic set of seven basic tools needs to be updated and expanded, and more importantly, the way we think about those tools also needs to be updated and expanded. There's just so much more to it than tools. For starters, personal attributes are much more important than tools. And then there's the daily management structures and information systems supporting problem‐solving, which are again more important than tools. I've argued further that a culture of critical thinking is at the core of a problem‐solving system, connecting this group of components into a functioning system. That culture of critical thinking is, yes, more important than tools. And all of that depends on engaged and effective leadership, which is, you guessed it, also more important than tools.

So however you answer the question "what are the basic tools of quality?," the answer is not as important as the ability of people to work with other people, a robust culture of data‐driven critical thinking, and the leadership and management structures that support that thinking across the organization. Effective problem‐solving requires a comprehensive system, not a checklist of tools, basic or otherwise.

CEO • MoreSteam

MoreSteam is the brainchild of Bill Hathaway. Prior to founding MoreSteam in 2000, Bill spent 13 years in manufacturing, quality and operations management. After 10 years at Ford Motor Co., Hathaway then held executive level operations positions with Raytheon at Amana Home Appliances, and with Mansfield Plumbing Products.

Bill earned an undergraduate finance degree from the University of Notre Dame and graduate degree in business finance and operations from Northwestern University's Kellogg Graduate School of Management.