Top 10 Lessons Learned From Process Improvement Leadership

Updated May 19, 2025

This post was originally published on January 24, 2018. It has been updated to reflect current insights and examples.

Looking back on over two decades of working with global organizations of every flavor, we've seen a lot of well-intentioned efforts to build systems of process improvement fall short of sustained success. Operational excellence is a complicated undertaking, and like baking a cake, missing any element of the recipe can lead to failure. At least when baking a cake you know that baking powder will always behave in a predictable way. A collection of people…not so much.

With apologies to Steve Harvey and David Letterman, here is our top ten list of lessons learned in the field while supporting several thousand corporate customers building process improvement systems:

1. Leadership cannot be delegated.

Successful and durable process improvement efforts depend on authentic senior leadership engagement, and "engaged" means that process improvement activities are on their calendar and on their "to do" lists — not an initiative that is assigned to others.

When leadership treats improvement as someone else’s responsibility, it quickly becomes a side initiative with no real traction. Improvement must be a visible, sustained commitment — not just endorsed in words, but reinforced through action. It belongs in strategy discussions, in meetings, and in daily behavior. Leaders model priorities by where they spend their time and attention.

This level of commitment echoes Deming’s emphasis on constancy of purpose and the need to embed quality into every part of the organization, not delegate it away. Leadership engagement is not about technical expertise, it is about presence: participating in the work of process improvement, questioning, reinforcing, and example-setting. Successful deployments are driven by leaders who embody improvement — not merely support it. As Steven Spears taught us years ago (The DNA of the Toyota Production System), the most successful systems are built when leaders teach the core concepts.

When senior leaders take ownership, they create energy, accountability, and momentum. When they step back, improvement becomes optional and optional efforts rarely endure.

2. Someone has to say: “We’re doing this.”

This is not an "organic" exercise at the beginning, and it takes a lot of energy to get a heavy thing moving. A certain amount of command authority is required to get things started. It may seem counter-intuitive when your goal is to build an empowered workforce, but you need a strong directive to re-orient people to value stream thinking. People don’t just spontaneously come together and decide to take on hard and messy challenges.

You’re asking people to change how they work, cross boundaries, and challenge old habits. That kind of shift begins with a directive, sometimes in response to a crisis that galvanizes everyone. Most important projects will cross functional boundaries, so leadership will need to enforce value stream values that put customers ahead of departmental priorities. That’s not going to happen unless someone says, “We’re doing this, and here’s how.”

Aurorium’s phased TRACtion implementation is a great example of pairing empowerment with structure—read about how their leaders aligned training, coaching, and accountability to accelerate adoption and results.

3. Align improvement efforts to the strategy of the business.

Identify the most important improvement work that must be undertaken to accomplish the organization’s strategic imperatives. There must be alignment between strategy and improvement work, or even with the best of intentions the wrong problems will be tackled.

It is just as important to match the right scope to the right objective. Ambition is good. But in process improvement, trying to fix everything at once often leads to fixing nothing at all. Broad scope leads to delays, wasted resources, and lost momentum. Teams get tired. Stakeholders lose interest. The project loses clarity.

The better approach is to prioritize smaller, tightly focused projects that can be executed quickly and deliver visible and meaningful results. Early wins build credibility. They teach the organization how to work inside the improvement framework and create a flywheel of trust and engagement.

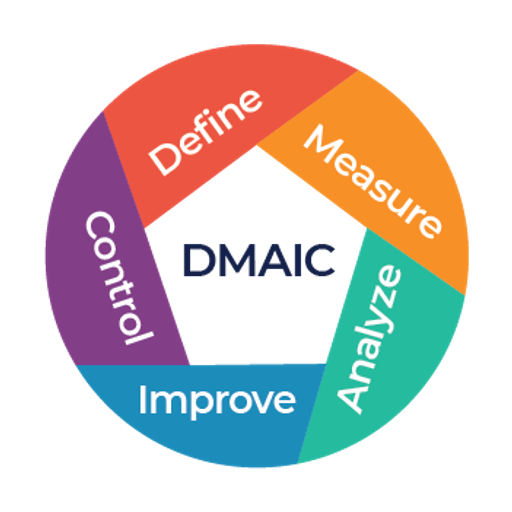

4. Make haste – the “M” in DMAIC does not stand for “months.”

Velocity matters. Don't let people get hung up on playing with tools at the expense of getting things done. One of the most common traps in early improvement efforts is overengineering the process by spending weeks in analysis, tinkering with tools, or chasing perfection before taking action.

DMAIC is structured, but it’s not meant to slow you down. “Measure” should quickly establish a baseline. If your process performs well below target, you probably don’t need an extremely precise measure of “screwed up”. “Analyze” should find root causes and drive decisions — not generate charts no one uses.

Leaders must create a sense of urgency while maintaining rigor. Progress is more important than perfection. The real value comes from delivering results, not from demonstrating technical mastery. The best project leaders know when to pause for insight and when it is time to move forward.

5. Pick the right people; not the available ones.

Don't pick the most available people to become project leaders. There's a reason why those people are available, and it’s not because they get things done. Make the functional leaders cough up their best people. Those people will get more done with the right attitude and good people skills than with a mastery of advanced technical methods.

The energy of volunteers is great, but process improvement roles are not parking spots for whoever happens to be free. They require initiative, credibility, and the ability to influence without authority. Push the functional leaders to nominate their top performers, even if it hurts.

Successful deployments start with putting the right people in the right roles. If you fill seats with whoever is available, expect to get the result you deserve for taking the easy path.

6. Don’t train without projects.

Don't train without projects! It's a total waste of time and money. Don't over-train, in advance, in batches. Try to pull as needed. Most improvement is accomplished with the most simple tools. The discipline to recognize problems from a customer perspective and address them head-on is more important than technical skills.

Training without a project is like practicing without a game. Skills fade. Lessons are forgotten. Enthusiasm dries up. Without real application, training becomes entertainment — an expensive one at that. And you’ll have nothing to show for it.

Train with purpose. Tie learning directly to solving real problems that matter. Pull people into training when the work demands it, not months before. The goal is not to build a warehouse full of certificates. The goal is to build capability that drives results.

Technical skills matter, but most projects that fail are unsuccessful due to organizational dynamics and other people issues. This is a team sport, so the ability to motivate other people is paramount.

7. Process improvement is not a conference room activity.

Get out of your office and go to Gemba, and remember the 3APs:

- Actual Place – Go to where the work happens (Gemba).

- Actual Process – Watch the work as it’s really performed, not just how it’s documented.

- Actual People – Talk to the people doing the work every day.

Improvement does not happen from behind a desk. It happens by standing where the work is done and seeing problems with your own eyes. The 3APs are simple, but most people skip them — and then wonder why nothing changes. Beware of Gembaphobia, the fear of going to where the work is actually performed. Tough problems cannot be solved without engaging the people involved in doing the work because they have invaluable insights about cause and effect. Ultimately, you’ll also probably need to convince those people to do something differently, and that convincing does not happen without authentic engagement.

Leaders who show up set the tone. Leaders who stay in their offices set the wrong one.

(Thanks to Jim Womack for coining the term "Gembaphobia".)

8. Don’t let an "expert-only" culture develop.

Avoid establishing a "Caste System" or "Expert Culture" where only experts can solve problems. Everyone can use these tools and this thinking in their daily work. Waiting for an "expert" can become a convenient excuse.

Improvement is not reserved for a certified few. When problem-solving is centralized, it slows everything down. Worse, it teaches employees to wait for permission instead of fixing problems themselves.

Process improvement tools are meant for everyone. Leaders must give people a shared language, sound critical thinking, a few core tools, and the confidence to act. Experts can coach, but real change happens when ownership is pushed out to the edges.

9. Silence is ultimately self-destructive.

Think about your operational excellence system as a business within the business. You’ll need a marketing function to tell the rest of the business what you are doing and why. That includes bragging about the wins! If senior leaders are consistently made aware of the ongoing savings and benefits, their support will be much more durable. And let’s face it, people doing process improvement work can be an easy target to meet a short term cost reduction goal.

The solution is to over-communicate. Share the vision. Explain the "why." Be clear about what is changing, what is not, and what success looks like. Invite questions. Surface concerns. Celebrate small wins loudly and often.

Transparency builds trust and moves improvement forward. Secret improvement efforts fail. Visible efforts create momentum across the organization.

10. Don’t overlook the middle.

Don't forget middle management. When teaching defense in basketball, an old adage is to “watch the waist” and ignore ball fakes or head fakes because nobody can move anywhere without their middle. It’s the same with organizations.

Middle managers are the critical link between strategy and execution. They are pulled in every direction — by executives demanding results, by teams needing support, and by customers expecting service. Without their buy-in, improvement efforts stall in the middle and go nowhere fast.

Leaders must make it easier for middle managers to win. Show them how process improvement helps them hit their targets, not just add to their workload. Make it clear that improvement is how they succeed, not just another “something extra”.

If you want real change to reach the front lines, you have to win over the middle first.

Final Thoughts

Process improvement is not just a methodology. It is a mindset, and it starts with leadership. The lessons above were not learned in theory. They were earned through years of real-world experience, across industries, teams, and challenges. Every organization’s journey looks different, but the themes stay the same: lead with intention, connect to the mission, stay grounded in practical results, and empower people at every level to make things better.

Successful improvement efforts follow a clear path:

- Set the Foundation — Leadership engagement and clear alignment to strategic priorities.

- Build the Right Team — Assign capable people and tie training directly to real work.

- Establish the Right Culture — Empower employees, stay grounded in the actual process, and bring middle management into the work.

- Maintain Momentum — Communicate constantly, celebrate progress, and reinforce the mindset that improvement is continuous, not perfect.

Skip a step, and improvement efforts stall, drift, or die. Organizations that follow the full path move faster, sustain change longer, and generate real impact not just short-term wins.

If your organization is serious about building stronger leadership alignment, driving real project execution, and creating lasting cultural momentum, we can help. Take a look at how MoreSteam's integrated training and technology tools can enable you to turn improvement into a way of operating — not just another program.

CEO • MoreSteam

MoreSteam is the brainchild of Bill Hathaway. Prior to founding MoreSteam in 2000, Bill spent 13 years in manufacturing, quality and operations management. After 10 years at Ford Motor Co., Hathaway then held executive level operations positions with Raytheon at Amana Home Appliances, and with Mansfield Plumbing Products.

Bill earned an undergraduate finance degree from the University of Notre Dame and graduate degree in business finance and operations from Northwestern University's Kellogg Graduate School of Management.